NYC Builders Are Converting Shuttered Migrant Hotels Into Apartments

A developer and a nonprofit hope to turn the Stewart Hotel in Midtown into 535 affordable residences. Photo: Shannon Stapleton/Reuters

New York City developers are seizing an unusual opportunity: converting at least a dozen hotels that housed migrants into new apartments.

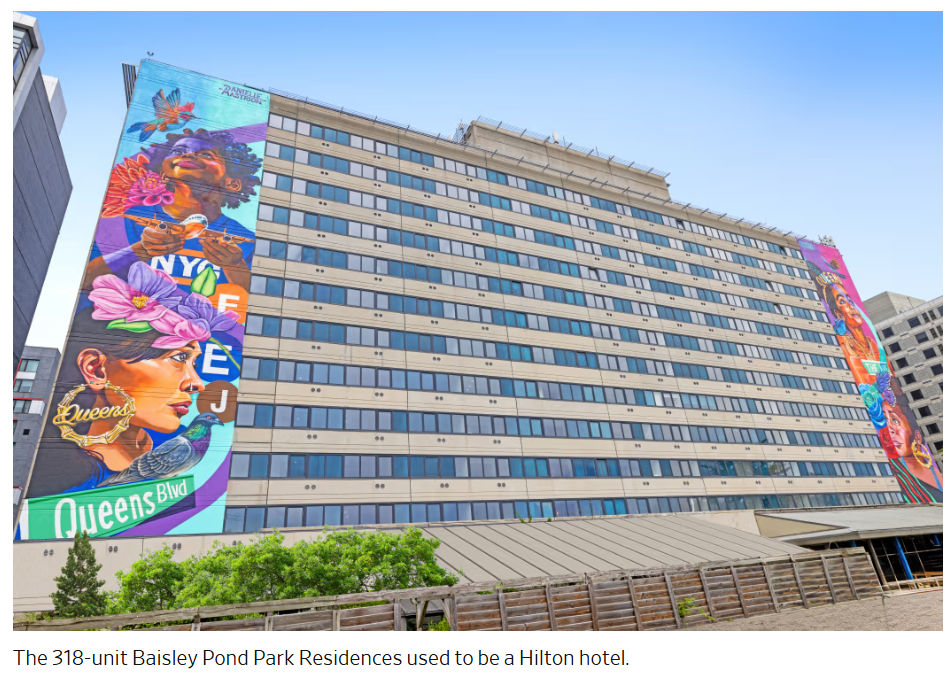

In Queens, a former Hilton near JFK airport is reopening as affordable housing. In Manhattan’s Financial District, the world’s tallest Holiday Inn is becoming for-profit student housing. In Midtown Manhattan, a developer is transforming a 600-key hotel into more than 500 residential units.

In all, developers are already poised to create more than 1,100 apartments from former hotels. Over a dozen more hotels could work as affordable housing conversions, said David Schwartz, co-founder and principal of multifamily developer Slate Property Group.

“Really, the opportunity is right now,” said Schwartz, who redeveloped the JFK Hilton into the 318-unit Baisley Pond Park Residences.

The final tally of hotel to residential conversions could be considerably higher. Vijay Dandapani, president of the Hotel Association of New York City, estimates that no more than 40% of the 160 hotels used as migrant shelters will reopen to the commercial market, mainly because of poor conditions and a hotel market recovering from the pandemic.

Many of these properties will be converted back to hotels or other commercial uses. But residential conversion is often the most likely alternative.

The lack of housing, especially affordable housing, has become a flashpoint in this year’s mayoral election. New York City rents stand at all-time highs and the vacancy rate hit a historic low of 1.4%. Zohran Mamdani’s pledge to freeze rent on rent-stabilized apartments helped propel him to victory in June’s Democratic primary for mayor.

Now, these conversions create an unexpected opening for the city to add housing. Even though the new units won’t do much to narrow the city’s overall housing shortage, developers said that conversions will play an important part in revitalizing stagnant neighborhoods by bringing in new residents and boosting local businesses there.

New York City has spent $8 billion to house migrants since 2022, to comply with the city’s legal obligation to provide shelter to all unhoused individuals.

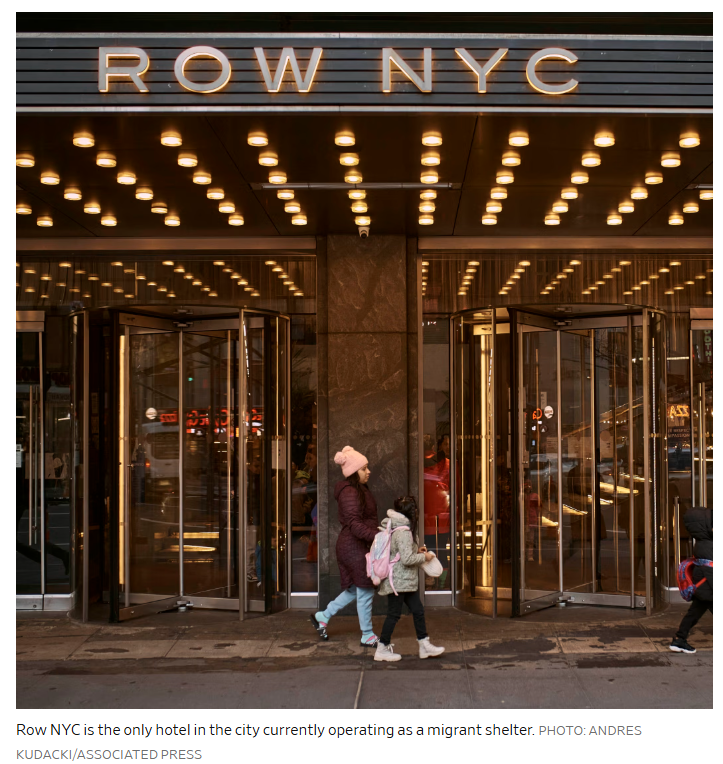

At the peak in early 2024, over 54,000 migrants were staying in the city’s hotels. The number of new arrivals in New York declined since 2024, allowing the city to close all but four emergency shelters housing migrants. The only hotel in the city currently operating as a migrant shelter is Row NYC, a 1,331-room hotel in Midtown with over 3,490 individuals, according to a city official.

Hotels work well for residential conversions because each unit has a bathroom and natural light, in contrast with an office building, where developers often need to cut out the center of the building to give each unit a window.

Schwartz said hotels can be converted in about half the time it takes to build apartments from scratch, and for a lower price. Still, a complex web of zoning and building code restrictions presents hurdles to residential conversion.

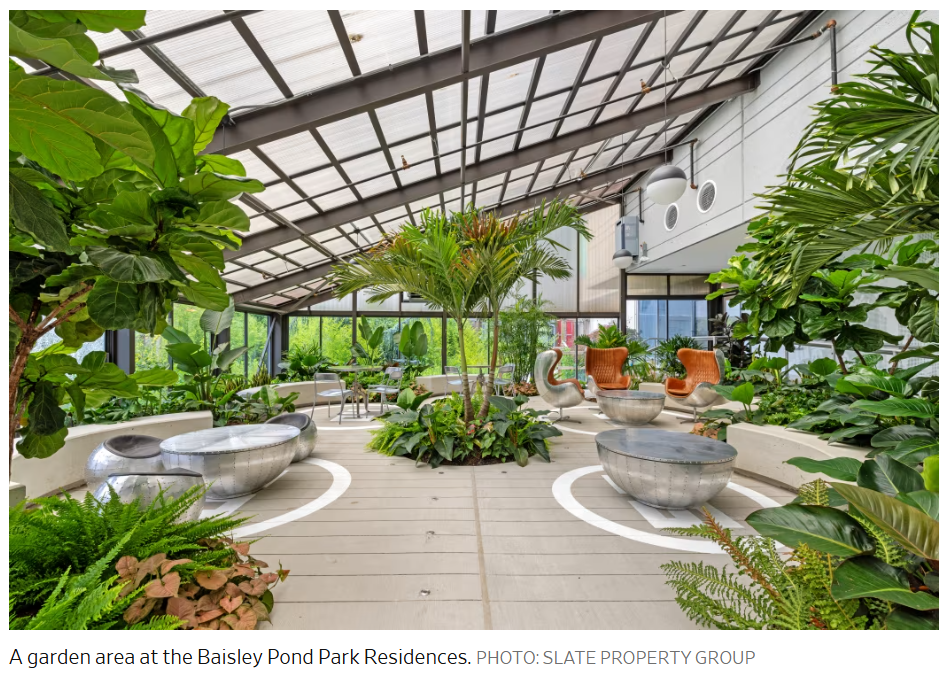

Slate and its nonprofit partner, RiseBoro Community Partnership, looked at over 50 properties before purchasing the JFK Hilton, which they chose for its affordability, zoning and large common spaces. Structural aspects of the hotel, like the number of hallways and bathrooms, sped the 19-month construction along. The most difficult aspect of the conversion was installing kitchenettes.

The low cost of redevelopment allowed the partners to reserve over half of the affordable units for people who are formerly homeless. The property’s large common areas accommodate on-site social services, and RiseBoro plans to use the industrial kitchen for job training.

Slate is also partnering with the nonprofit Breaking Ground to convert the Stewart Hotel into 535 affordable residences after their purchase is finalized. The partners chose the Stewart for its proximity to Penn Station, which they said will help some tenants access jobs. Construction is anticipated to take less than two years.

By combining three hotel rooms—commonly around 300-square-feet each—developers can build a one-bedroom condo or two studios.

Hotel owners are often happy to sell or convert for a more profitable use rather than invest as much as $100,000 per room to reopen, said Michelle Russo, CEO of the consulting firm hotelAVE.

The stigma of being used as a shelter presents another concern—and cost—for hotels, she said. “It has to relaunch as something totally different.”

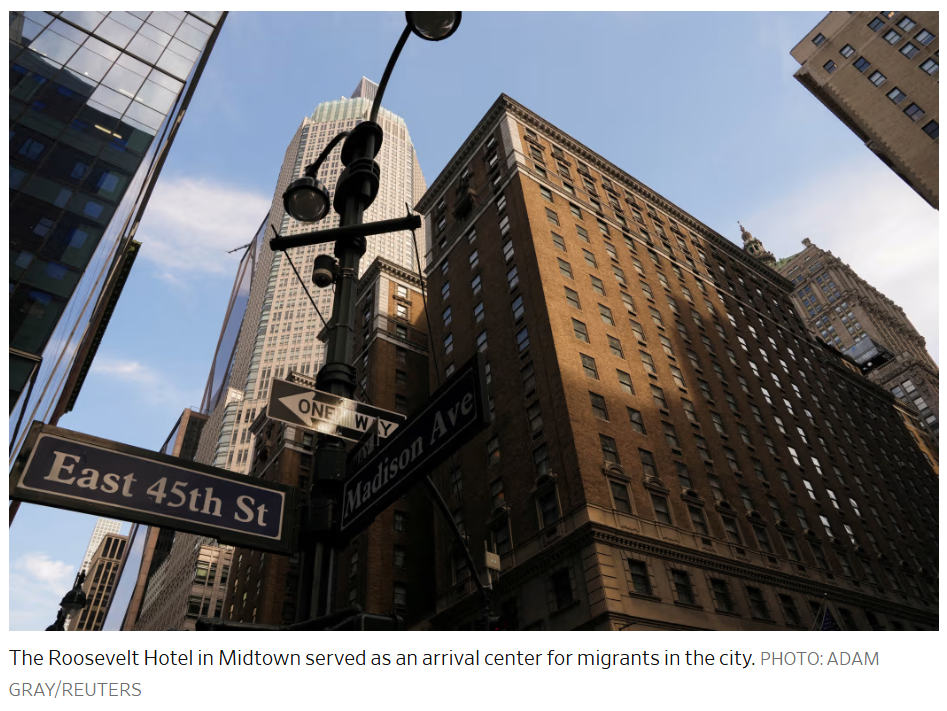

One of the largest and most prominent migrant shelters in the city is unlikely to reopen or convert to an all-residential complex, according to several analysts. The Roosevelt Hotel, over 1,000 rooms consuming a block of prime real estate in Midtown Manhattan, processed over 173,000 migrants as the city’s arrival center. The shelter closed in late June.

The hotel is controlled by the government of Pakistan, which has indicated interest in a joint-venture redevelopment. The hotel could convert to offices or mixed use, developers said.

For the hotels that do reopen, the addition of a few thousand rooms is unlikely to dampen the city’s strong hotel market, said Sean Hennessey, consultant and associate professor at NYU’s Tisch Center of Hospitality.

Efforts to turn hotels into affordable housing in New York City have faltered in the past. In 2021, the state legislature passed the Housing Our Neighbors With Dignity Act, which helps fund affordable housing conversions, but strict zoning and housing code regulations have posed challenges. The Baisley Pond Park Residences is the first conversion using funding from the act.

“I think we really missed a big opportunity as a city when the temporary Covid buildings that were being used for transitional housing closed,” Schwartz said. “We’re hoping that can happen now.”